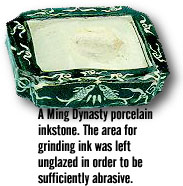

Abrasive

Treasure (page 3)

Photos Courtesy of The National

Palace Mesuem

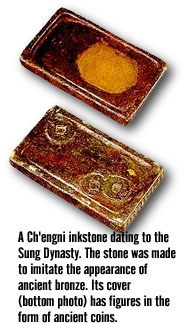

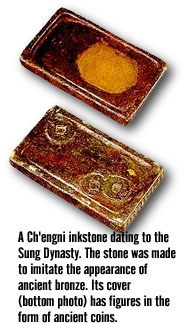

The Ch'engni inkstone (¡q¼áªdµx) is considered

the best of all the ceramic types. Gaining popularity during the T'ang

Dynasty (618-907), it was by far the most difficult of all inkstones, ceramic

or otherwise, to manufacture. According to historical records, first a

cloth bag was suspended in a running stream.  After

approximately one year, the bag was removed from the water, by which time

fme silt had gathered in the bag. Small rocks and other impurities were

then filtered out, and the remaining silt dried in the sun. It was next

mixed with huang tan t'uan ( ¶À¤¦¹Î), a resinous plant substance, and kneaded

together. After being shaped in a mold and decorated with a knife, it was

removed from the mold, placed in a bag containing rice husks and cow manure,

and hung in a dark, cool place to dry. It was later fired in a ceramic

kiln for approximately ten days. After cooling, it was covered with black

wax, submerged in a vat of rice vinegar, and finally steamed over high

heat about a half dozen times.

After

approximately one year, the bag was removed from the water, by which time

fme silt had gathered in the bag. Small rocks and other impurities were

then filtered out, and the remaining silt dried in the sun. It was next

mixed with huang tan t'uan ( ¶À¤¦¹Î), a resinous plant substance, and kneaded

together. After being shaped in a mold and decorated with a knife, it was

removed from the mold, placed in a bag containing rice husks and cow manure,

and hung in a dark, cool place to dry. It was later fired in a ceramic

kiln for approximately ten days. After cooling, it was covered with black

wax, submerged in a vat of rice vinegar, and finally steamed over high

heat about a half dozen times.

The color of the finished inkstone depended on the area of production

and other variables such as the temperature of the kiln. If the last couple

of production steps sound like a page from the Chinese culinary arts, then

the names given to the different colors of inkstones are off the menu of

a seafood restaurant. These include, among others, "shrimp head red,"

"crab shell blue," "eel orange," and ''fish stomach

white." The final appearance of the Ch'engni inkstone was very similar

to that of stone, and supposedly equally as hard. It had a metallic sound

to it when struck, and even a steel knife could not scratch its surface.

Although these inkstones were highly regarded at the time, difficulty of

production was no doubt partially responsible for their growing scarcity

after the T'ang Dynasty.

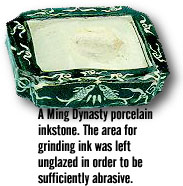

By the Sung Dynasty (960-1279), inkstones once more started to be made

almost exclusively of stone. This reflect- ed the mature artistic expression

of the Sung period, where the emphasis was no longer on complexity of manufacture,

but on the simple and refined beauty of natural stone. The preference has

en- dured up to the present day.

Clearly, not just any stone could be used to make an inkstone because

of aes- thetic and practical considerations. Ac- cording to the History

of the Inkstone written by Mi Fei (¦Ìªè ), the Sung schol- ar, calligrapher,

and fanatic collector of inkstones, stones from thirteen different regions

of China were used in the manu- facture  of

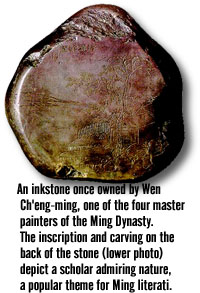

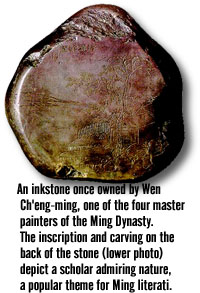

inkstones. In addition, ink- stones were embellished with carving, both

with designs and calligraphy. Elevated from the status of utilitarian items,

good inkstones were cherished as works of art in themselves. It was during

the Sung that the inkstone, along with brush, inkstick, and paper, was

given the accolade of the "four treasures of the scholar's study."

of

inkstones. In addition, ink- stones were embellished with carving, both

with designs and calligraphy. Elevated from the status of utilitarian items,

good inkstones were cherished as works of art in themselves. It was during

the Sung that the inkstone, along with brush, inkstick, and paper, was

given the accolade of the "four treasures of the scholar's study."

Not all stones are created equal, and of all the areas which produced

inkstones during the Sung, three were considered to be the best: those

from Tuanchou ( ºÝ¦{), Hsichou (¾ù¦{), and Ch'ingchou ( «C¦{). Before long,

stones from Ch'ing- chou were unobtainable, and those from Yaoho (¬«¦{)

were considered equally valuable. Together with the Ch'engni inkstone,

which was still produced in limited numbers during the Sung, the four were

crowned as China's most famous inkstones. Today, a millennium later, these

are still considered the best by antique collectors. Moreover, the ink-

stones from the area formerly known as Tuanchou and Hsichou are still being

produced by contemporary craftsmen.

Foreword and Preface

The Brush: Unaltered Craftsmanship

The Inkstick: Black Soil

Artistry

Paper: The Basic Fiber of Communication

The Inkstone: Abrasive

Treausre

The Inkstone: Unparalleled

Connaisseur

Accessories For The Studio:

Functional Artistry

for questions and comments please send to liaoless@iii.org.tw

By Jeffrey H. Mindich

Published by the Council for Cultureal Affairs Executive Yuan Republic

of China

After

approximately one year, the bag was removed from the water, by which time

fme silt had gathered in the bag. Small rocks and other impurities were

then filtered out, and the remaining silt dried in the sun. It was next

mixed with huang tan t'uan ( ¶À¤¦¹Î), a resinous plant substance, and kneaded

together. After being shaped in a mold and decorated with a knife, it was

removed from the mold, placed in a bag containing rice husks and cow manure,

and hung in a dark, cool place to dry. It was later fired in a ceramic

kiln for approximately ten days. After cooling, it was covered with black

wax, submerged in a vat of rice vinegar, and finally steamed over high

heat about a half dozen times.

After

approximately one year, the bag was removed from the water, by which time

fme silt had gathered in the bag. Small rocks and other impurities were

then filtered out, and the remaining silt dried in the sun. It was next

mixed with huang tan t'uan ( ¶À¤¦¹Î), a resinous plant substance, and kneaded

together. After being shaped in a mold and decorated with a knife, it was

removed from the mold, placed in a bag containing rice husks and cow manure,

and hung in a dark, cool place to dry. It was later fired in a ceramic

kiln for approximately ten days. After cooling, it was covered with black

wax, submerged in a vat of rice vinegar, and finally steamed over high

heat about a half dozen times.

of

inkstones. In addition, ink- stones were embellished with carving, both

with designs and calligraphy. Elevated from the status of utilitarian items,

good inkstones were cherished as works of art in themselves. It was during

the Sung that the inkstone, along with brush, inkstick, and paper, was

given the accolade of the "four treasures of the scholar's study."

of

inkstones. In addition, ink- stones were embellished with carving, both

with designs and calligraphy. Elevated from the status of utilitarian items,

good inkstones were cherished as works of art in themselves. It was during

the Sung that the inkstone, along with brush, inkstick, and paper, was

given the accolade of the "four treasures of the scholar's study."