Abrasive

Treasure (page 2)

Photos Courtesy of The National

Palace Mesuem

Although a small charcoal

fire could be lit under bronze and iron inkstones, preventing the ink from

freezing during cold north China winters, they also proved less than ideal

for grinding ink.

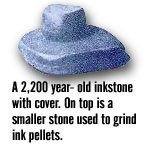

New archaeological discoveries constantly push the earliest believed

date for the use  of

inkstones further back into Chinese antiquity. In 1975, archaeologists

uncovered an inkstone from an ancient tomb in the Yunmeng (¶³¹Ú) area of

Hupeh Province. It proved to be approximately 2,200 years old, dating back

to the Ch'in Dynasty (221-206 B.C.). This particular discovery was important

because it yielded the first inkstone dated to before the Christian era.

But archaeologists were soon to move the date back much further.

of

inkstones further back into Chinese antiquity. In 1975, archaeologists

uncovered an inkstone from an ancient tomb in the Yunmeng (¶³¹Ú) area of

Hupeh Province. It proved to be approximately 2,200 years old, dating back

to the Ch'in Dynasty (221-206 B.C.). This particular discovery was important

because it yielded the first inkstone dated to before the Christian era.

But archaeologists were soon to move the date back much further.

Only five years later, a phenomenal archaeological find made international

news: the discovery of an inkstone over 5,000 years old. Excavated at the

Lintung Chiangchai Neolithic site ( Á{¼à«¸¹ë¿ò§}), just fifteen kilometers

from the famous Panp'o Neolithic site ( ¦è¦w¥b©Y¿ò§}) at Sian, Shensi Province,

it is dated to the early part of the Yangshao Neolithic pottery culture

( ¥õ»à¤å¤Æ).

Uncovered together with the inkstone were ink pellets and a ceramic

waterpot, both used with the inkstone. China did not have a written language

at that early date, but archaeologists have long believed that many of

the designs on the painted pottery from that time were done with a brush.

The excavated brush, together with the inkstone, ink, and waterpot, constitutes

a complete Neolithic painting set, and remains the earliest predecessor

of three of the scholar's "four treasures" found so far.

Despite its ancient age, the inkstone excavated from the Chiangchai

site is anything  but

primitive. It has a cover, and a depressed surface for grinding the ink.

It therefore closely resembles the inkstones familiar several millennia.

later. This early inkstone, however, like the one uncovered in Yunmeng,

was used in a somewhat different manner from later inkstones because of

the form of ink. The ink pellets found with these early stones were too

small to be held in the hand and ground like more recent inksticks. Instead,

both of these early discoveries were found with another stone shaped like

a pestle; the ink was ground by putting an ink pellet on the surface of

the larger inkstone, then the smaller pestle was used to grind the ink

pellet.

but

primitive. It has a cover, and a depressed surface for grinding the ink.

It therefore closely resembles the inkstones familiar several millennia.

later. This early inkstone, however, like the one uncovered in Yunmeng,

was used in a somewhat different manner from later inkstones because of

the form of ink. The ink pellets found with these early stones were too

small to be held in the hand and ground like more recent inksticks. Instead,

both of these early discoveries were found with another stone shaped like

a pestle; the ink was ground by putting an ink pellet on the surface of

the larger inkstone, then the smaller pestle was used to grind the ink

pellet.

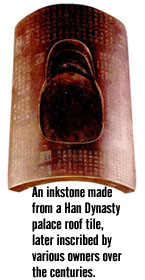

Other discoveries have shown that by the advent of the Christian era

stonewas no longer used for the manufacture of inkstones. For almost a

millennium, ceramic became the material of choice. However, these inkstones

were very dif- ferent from other ceramic ware of the time. Ceramic roofing

tiles from Chinese palaces provided an unusual yet very suitable material

for making inkstones. Rectangular in shape and curved like a quarter moon,

a small ink well and water reservoir was chiseled out of the center of

the tile. For greater durability, these roof tiles were fired in kilns

at higher temperatures than ordinary ceramic ware, producing a fne, hard

surface. Ink- sticks could be easily ground on this type of inkstone, which

had the added quality of not damaging brushes or retarding the evaporation

of ground ink.

Foreword and Preface

The Brush: Unaltered Craftsmanship

The Inkstick: Black Soil

Artistry

Paper: The Basic Fiber of Communication

The Inkstone: Abrasive

Treausre

The Inkstone: Unparalleled

Connaisseur

Accessories For The Studio:

Functional Artistry

for questions and comments please send to liaoless@iii.org.tw

By Jeffrey H. Mindich

Published by the Council for Cultureal Affairs Executive Yuan Republic

of China

of

inkstones further back into Chinese antiquity. In 1975, archaeologists

uncovered an inkstone from an ancient tomb in the Yunmeng (¶³¹Ú) area of

Hupeh Province. It proved to be approximately 2,200 years old, dating back

to the Ch'in Dynasty (221-206 B.C.). This particular discovery was important

because it yielded the first inkstone dated to before the Christian era.

But archaeologists were soon to move the date back much further.

of

inkstones further back into Chinese antiquity. In 1975, archaeologists

uncovered an inkstone from an ancient tomb in the Yunmeng (¶³¹Ú) area of

Hupeh Province. It proved to be approximately 2,200 years old, dating back

to the Ch'in Dynasty (221-206 B.C.). This particular discovery was important

because it yielded the first inkstone dated to before the Christian era.

But archaeologists were soon to move the date back much further.

but

primitive. It has a cover, and a depressed surface for grinding the ink.

It therefore closely resembles the inkstones familiar several millennia.

later. This early inkstone, however, like the one uncovered in Yunmeng,

was used in a somewhat different manner from later inkstones because of

the form of ink. The ink pellets found with these early stones were too

small to be held in the hand and ground like more recent inksticks. Instead,

both of these early discoveries were found with another stone shaped like

a pestle; the ink was ground by putting an ink pellet on the surface of

the larger inkstone, then the smaller pestle was used to grind the ink

pellet.

but

primitive. It has a cover, and a depressed surface for grinding the ink.

It therefore closely resembles the inkstones familiar several millennia.

later. This early inkstone, however, like the one uncovered in Yunmeng,

was used in a somewhat different manner from later inkstones because of

the form of ink. The ink pellets found with these early stones were too

small to be held in the hand and ground like more recent inksticks. Instead,

both of these early discoveries were found with another stone shaped like

a pestle; the ink was ground by putting an ink pellet on the surface of

the larger inkstone, then the smaller pestle was used to grind the ink

pellet.