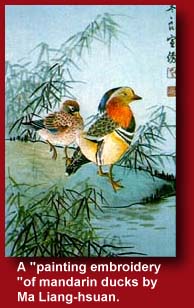

Under the impact of the popular yuan t'i school of court painting, "painting-embroidery" and "calligraphy-embroidery," which uses needles and flosses instead of brushes and pigments, came into vogue. Unlike the works of previous dynasties, most of these Sung works have unembroidered backgrounds; only the featured subjects were done in satin stitch.

As time passed, this new embroidery fashion diverged further from the

practical uses of folk embroidery styles and became more closely aligned

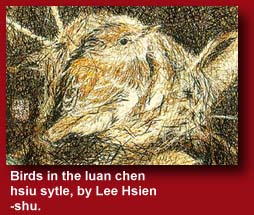

with painting. The most favored motifs were renditions of flowers and birds,

landscapes, and human figures. Eventually, the trend enveloped direct embroidery

of sketches made by painters. The embroiderer was responsible for adding

the texture and color. During one period, flower and bird paintings by

Huang Ch'uan (903-965), and calligraphic works by Su Shih (1036-1101) and

Mi Fei (1057-1101) were especially popular embroidery subjects. Since "painting-embroidery"

imitates paint or ink pigment applications, a great variety of stitches

and intricate coloring effects were developed to catch the vivacity of

the original. Sometimes 15 types of flat stitches were employed in such

Sung Dynasty works.

These stitches were also used in folk embroidery during the same period. In addition, there was a popular folk form known as ch'uo sha, which counted off the interstices on the grid of the gauze background material and then wove designs using a cross stitch. These stitch forms had great influence on the later development of Chinese embroidery. In fact, during the T'ang and Sung Dynasties, there was continuous expansion in the types of stitches employed in folk embroidery, and its creative vigor gave new impetus to the development of embroidery as art.

The rise of Buddhist Lamaism during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) drew embroidery back again to religious themes. In this period, extensive use of gold and silver threads made the works especially luxurious. Unfortunately, few examples of Yuan Dynasty embroidery survive.

The Ming Dynasty ushered in a new epoch for embroidery, as tastes once

again departed from religious themes. Forms became more ornate. Apart from

the traditional silk and gold threads, embroidery materials now included

such items as pearls, down from the tail feathers of Siamese fighting cocks,

and even human hair. Ming Dynasty color tastes contrasted strongly with

the mellow tints handed down from the Sung Dynasty. In general, stronger,

more luxuriant colors were preferred, and sometimes the artist's brush

added color to empty space in embroidered pieces, blending the two arts

in a new way.

The most famous embroidery style of the Ming Dynasty was ku hsiu, (embroidery of the Ku family), an innovation of Ku Hui-hai's concubine, Madame Miao. This style was celebrated for the unique results gained from using a wide assortment of needles, employing unusually rich color gradations, and emphasizing disciplined neatness of stitching. Madame Miao's masterpiece, A Picture of Eight Steeds, was considered to be on a level with the famous work of Yuan Dynasty horse-painter Chao Tzu-ang. Her successor, Han Hsi-meng, wife of Ku Shou-chien, was f'amous f'or her embroidery of flower and bird themes. Han's elegant album of embroidery, imitating famous Sung and Yuan paintings, is a masterpiece.

Stimulated by the evident popularity of ku hsiu, embroidery became a fashionable market item. Throughout the Ming and Ch'ing Dynasties, private embroidery workshops could be found throughout the empire. The market f'or excellent embroidery became highly competitive, further encouraging innovation. Local embroidery motifs and stitching techniques emerged like bamboo shoots after a spring rain. By the end of the Ch'ing Dynasty, a rich variety of regional embroidery styles emerged.

Ancient Bronzes:

Early Design Elegance

Bronze Mirrors: Aesthetic

Reflections

Buddist Caves: Compassionate

Serenity

Stone Collecting: Miniature

Landscapes

Snuff Bottles: Art In Small

Packages

Embroidery: Meticulous

Masterpieces

for questions and comments please send to liaoless@iii.org.tw

![]()

publisher: Kuo Wei-fan

Organizer: Council Cultural Affairs and Development, Kwang Hwa Publishing

Company

Supervisor: Liu Li-min

Coordinators: Huang Su-Chuan, Yiu yu-fen

Managing Editor: Chen Wen-tsung

Editor: Richard R. Vuylsteke

Reader: Ching-Hsi Perng

Published by the Council for Cultureal Affairs

Executive Yuan Republic of China