While there had been a few half-hearted attempts before, the U.S. entry into the world's fair sweepstakes came on the 100th anniversary of the birth of the republic. Philadelphia was the natural site for this Centennial Exhibition, which centered on a vast machinery hall, holding 13 acres of new devices, widgets, and gadgets.

One of the most popular exhibits in the Machinery Hall was a prototype slice of the cable that Roebling Brothers would use for the Brooklyn Bridge. They would end up using 6.8 million pounds of these first galvanized cables, covered with Zinc and with a strength of 160,000 pounds per square inch (double that of the iron wire used at Niagara).

The Machinery Hall also featured other novelties, such as the first typewriter and a telephone. The Emperor Dom Pedro of Brazil put Bell's strange device to his ear, then quickly dropped it, exclaiming "My God, It talks!" [footnote here]

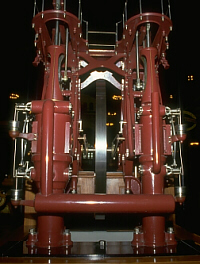

Telephones and typewriters were nice, but what people wanted

was power. Towering over the hall was the gigantic Corliss

Steam Engine, taller than a house, powering 13 acres of

machinery in the great hall.

The 1500 horsepower double Corliss steam engine connected

to 5 miles of shafting used to move this power throughout

the vast machinery hall.

[Hunter,, pp. 207-208]

Telephones and typewriters were nice, but what people wanted

was power. Towering over the hall was the gigantic Corliss

Steam Engine, taller than a house, powering 13 acres of

machinery in the great hall.

The 1500 horsepower double Corliss steam engine connected

to 5 miles of shafting used to move this power throughout

the vast machinery hall.

[Hunter,, pp. 207-208]

On opening day, the hall was full of people, but dead silent as President Ulysses S. Grant and the Emperor Dom Pedro of Brazil climbed up on the engine platform and hit the levers that allowed steam into the cylinders. The engine hissed and the floor trembled. Then, the huge walking beams slowly started moving up and down, feeding the giant flywheel which spun around, gaining momentum and storing energy. Then, belts started moving, and shafts and pulleys started turning as power went out into the hall.

The amount of activity in the hall boggled people's minds. The

New York Herald, the Sun, and the Times all printed their daily

editions in the hall. Machines started sewing, pins got stuck

into paper, wallpaper printed, logs were sawed. What really

amazed people, though, was the Corliss Engine. The machine

had only one attendant, who sat calmly on the platform and

read newspapers.

[McCullough,, pp. 351-352]

Clasp lockers (they weren't called zippers for 30

more years) were shown in Chicago in 1893 by the inventor

Whitcomb Judson and his partner Lewis Walker. They

paraded around in boots made with

the clasp locks, a tradition that is reminiscent of the

current velcro and sneaker fad.

The next year they formed the Universal Fastener Company and

the modern zipper came into being.

[Petroski,, pp. 100-101]

The amount of activity in the hall boggled people's minds. The

New York Herald, the Sun, and the Times all printed their daily

editions in the hall. Machines started sewing, pins got stuck

into paper, wallpaper printed, logs were sawed. What really

amazed people, though, was the Corliss Engine. The machine

had only one attendant, who sat calmly on the platform and

read newspapers.

[McCullough,, pp. 351-352]

Clasp lockers (they weren't called zippers for 30

more years) were shown in Chicago in 1893 by the inventor

Whitcomb Judson and his partner Lewis Walker. They

paraded around in boots made with

the clasp locks, a tradition that is reminiscent of the

current velcro and sneaker fad.

The next year they formed the Universal Fastener Company and

the modern zipper came into being.

[Petroski,, pp. 100-101]

To preserve the results of the Centennial Exhibition, the Smithsonian Institute built it's second building on the Washington, Mall, The Arts and Industries Building still contains many replicas of the devices in the Machinery Hall, including a model of the great Corliss Engine.

Sources

Louis C. Hunter and Lynwood Bryant, A History of

Industrial Power in the United States, 1780-1930. Vol

3: The Transmission of Power

MIT Press (Cambridge, MA, 1991), p. 207-208.

David McCullough, The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the

Building of the Brooklyn Bridge,

Touchstone Books (New York, 1972), pp. 351-352

Henry Petroski, The Evolution of Useful Things,

Knopf (New York, 1992), pp. 100-101.